The Great food transformation: Turning the problem into a solution?

So, is the planetary health diet the diet to save the world? Will it feed the future population of 10 billion people within the planetary boundaries? Yes, science now shows that this should be possible! That is, if we adopt the planetary health diet on a global scale. However, there are several important things to note. First, the authors of the report show that even small increases in meat and dairy consumptions from the suggested ranges would make it difficult or impossible. Secondly, it becomes increasingly unlikely to be able to produce healthy food from sustainable food production past this population limit. Thirdly, change in diet alone will not suffice. We will also need to halve food loss and waste, and substantially improve food production practices. The whole food system needs to be revised –we need a Great Food Transformation, as the authors put it. In the last section of the report, they set scientific targets for the required food system reform and describe how they could be achieved, ultimately improving global health and securing our common future on planet Earth.

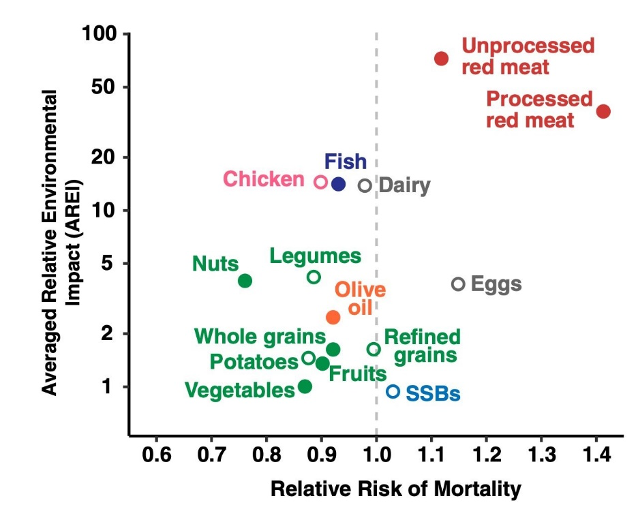

Most importantly, we will need a shift in attitudes. Studies have shown that people are more willing to change behaviour for health than for environment. Interestingly, even though they created the planetary health diet solely based on optimizing human health (and didn’t even consider sustainability or environmental effects at this point), they found that it fit within the five planetary boundaries they assessed. Indeed, health and environmental effects of foods often go hand in hand (Figure 1). Luckily, we don’t have to choose between them. What is healthy is usually good for the planet too.

Figure 1. Association between a food group’s impact on mortality and environment. The y axis is on a log scale and is the AREI of producing a serving of each food group across 5 environmental outcomes relative to the impact of producing a serving of vegetables (not including starchy roots and tubers). The x axis is the relative risk of mortality. A relative risk > 1 indicates that consuming an additional daily serving of a food group is associated with increased mortality risk, and a relative risk < 1 indicates that this consumption is associated with lowered mortality risk. In green = minimally processed plant-based foods; dark blue = fish; gray = dairy and eggs; pink = chicken; red = unprocessed red meat (beef, lamb, goat, and pork) and processed red meat; light blue = sugar-sweetened beverages; and orange = olive oil. Food groups associated with a statistically significant change in risk of mortality (at P < 0.05) are denoted by solid circles. Non-significant associations are denoted by open circles. Source: Clark, M. A. et al., 2019.

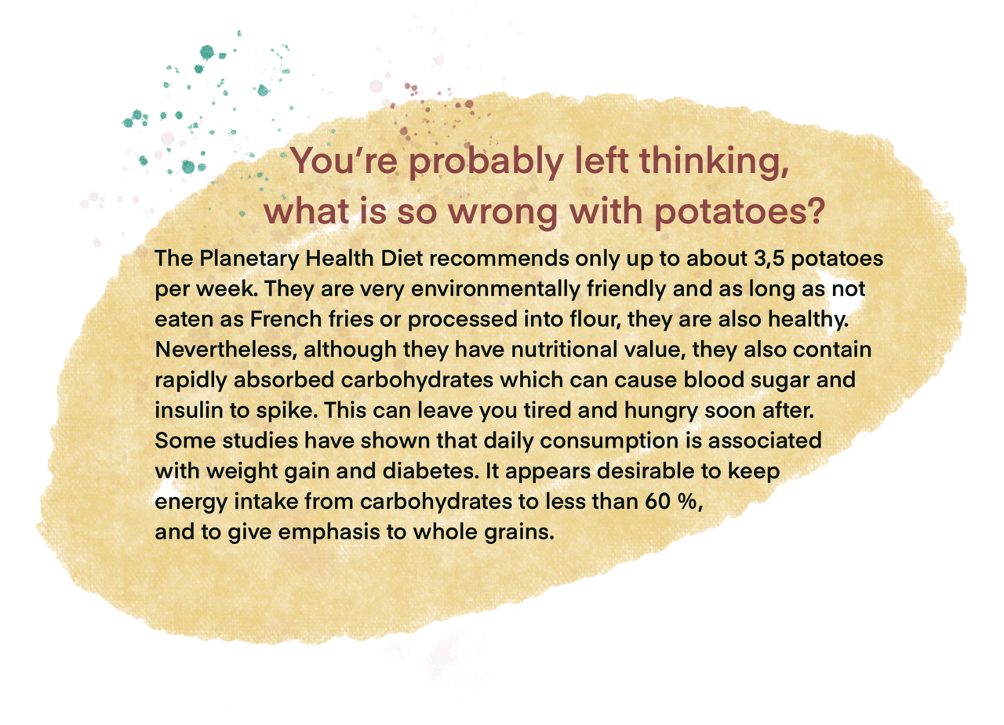

As stated in the EAT-Lancet report: “Food in the Anthropocene represents one of the greatest health and environmental challenges of the 21st century.” To reach the targets, the authors emphasize that we will need unprecedented global collaboration and commitment. Both hard measures, such as taxation or regulation, and soft measures, such as public awareness campaigns, will be necessary. This calls for action at all levels and sectors. Local adaptations of the planetary health diet that are culturally acceptable are required. Many countries have already revised their food recommendations, and the Finnish version should come out this year (2022). It will most likely have more potatoes, as compared to the reference diet, as they are a big part of our culture –we even have our own separate Potato Research Institute. Unfortunately, it is well known that people do not follow food recommendations. One of the most effective ways to change eating habits is to address the foods served at daycares, schools and workplaces. Through this, the healthier diet will become the norm in people’s minds.

Now as you can imagine, the report was not easy to digest by some from the meat industry. They will undoubtedly continue to do everything in their power to slow down the change required. Just like tobacco companies and the oil industry did when scientific facts were against them. It is important that scientists and media recognise and take seriously the issue of misinformation and content pollution, and do their best to fight it, especially in relation to topics fundamental for health and the environment. The role of education and awareness has become ever greater in our epoch of social media, where fake news spreads like a virus. Just look at how fast the #yes2meat movement organised itself before the launch of the EAT-Lancet report and rapidly dominated the online discussions in an unsettling way. Talking of viruses, shifting to less and better quality meat would also decrease the huge risks factory farming poses for new viruses to develop and spill over to humans, similarly to the current SARS-CoV-2. And there will be a new virus – and next time, it might be more deadly. A radical change in the food system would greatly alleviate this fear. Not to mention animal welfare and antimicrobial resistance, including antibiotic resistant bacteria.

It won’t be an easy task, and as we have seen, it is a heated topic full of emotion. Political will and combined effort are crucial. Nevertheless, it is possible! In 1987 the world’s nations were quick to act on the scientific evidence of the depletion of the ozone layer (one of the planetary boundaries), politically committing to shrink the ozone hole. It now looks like it could heal by 2050. The joint international opposition to the current 2022 war in Ukraine is a recent example of how we can come together and act promptly when we face a common threat. As for shifting diets, Finland is actually mentioned in the EAT-Lancet report, as an example of a country in which we have already previously managed to change dietary patterns, referring to the successful North Karelia Project.

We can already see signs of a shift. The shop shelves are displaying increasing numbers of plant protein products. New products aiming to convince devoted meat-eaters are popping up, such as Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat. Even some meat and dairy companies have acknowledged and embraced the trend by introducing plant-based products. Companies are racing to produce in-vitro meat from cultured animal stem cells – for which the nutritional values are more readily modifiable than those of traditional meat. Vegetarian days are being introduced to schools and pricing at, for example, Unicafe reflects environmental impact. What’s best, we can all participate by respecting our food, aiming to have lots of colour and variety on our plates, favouring what’s in season, and sticking to less but better quality. As Johan Rockström puts it in the World Changing Cookbook: “Not everyone can do everything, but if each and every one of us makes active choices for a healthier, more sustainable diet, then together we can achieve great things – for ourselves and for the planet!”

Thank you for reading!

Common misconceptions

Food transported from far is bad: The production accounts for most of the food’s climate impact, around 80 %. Transport accounts for only a relatively small proportion as food is mainly shipped on fuel-efficient ships or transported by land. Even road freight is relatively fuel-efficient. In fact, driving 50-60 km to a local farmer to buy a kilogram of veg will produce more emissions than what a fully laden lorry will produce for that same kilogram of freight over 90 000 km on the road. Food is seldom transported by air (but when it is, that does indeed make up a large fraction of its environmental impact). Environmentally speaking, it is not so much the transport one needs to think of when buying food, but its origin. Important aspects to consider are fresh water resources, biodiversity and chemical use. In many areas, agriculture poses critical stress on land and biodiversity.

Packaging is bad: Packaging is not all bad, especially when we dispose of it properly. It protects food, and ideally, reduces food waste. A rotten cucumber can cause the neighbouring cucumbers to rot as well if not wrapped. Again, it is the production that causes the most greenhouse gas emissions, and compared to it, packaging is a relatively small contributor. Organic products are often packaged to protect them from pesticides from other products.

Switching from meat to soy will destroy rainforests: Soy farming has been linked to tropical deforestation. However, most of the world’s soy is fed to livestock to produce meat, milk and eggs. So, the main problem with soy really lies in animal production. For example, in Brazil, much more forest has been cut down to make space for pasture (for meat production), than has been cut for soybean cultivation.

Finnish beef is climate friendly, “suomalainen (naudan)liha on ilmastoteko”: Climate friendliness is always relative. Relative to plant-based products, this statement is not true. Nevertheless, it may be true that Finnish beef is more environmentally friendly when compared to e.g., Brazilian beef raised on deforested land. However, this does not automatically make it good for the climate. Livestock still need to eat more calories than they produce, and cows still burp methane. So, compared to imported plant-based products, even the transportation emissions do not make the plant-based options worse (see above on transport). Compared to meat produced elsewhere, especially outside the EU, Finnish meat production uses less antibiotics, poses less pressure on freshwater resources and can in fact be important for our biodiversity as light grazing controls weeds and maintains vital habitats for plants and animals. However, to maintain biodiversity, a much smaller number of animals would be enough. This also means that completely ending cattle production in Finland would not be desirable, at least from the biodiversity perspective. Although, cows in Finland eat mainly grass, they still consume 30 % of all cereal produced in Finland. In Finland 70 % of all agricultural land is used for livestock (including their feed).

I can’t go vegan, so I might as well give up: Even the planetary health diet doesn’t require veganism, being actually quite far from it if you so wish. In western countries, typically any reduction in, e.g., the amount of meat consumed, is an improvement in terms of both human health and environmental impact. There is no need for absolutes, especially if such goals discourage any smaller changes. There’s a much bigger effect if lots of people reduce their use of animal products than if only a few become vegans.

Based on discussions related to the latest IPCC report (2022) and planetary boundaries, it looks like we’re already headed to the end of the world, so what’s the point? Opinions vary, but “the end of the world” is generally not what we can expect based on the scientific consensus. In terms of climate change, every tonne of greenhouse gases emitted warms the planet more. That also means that every reduction we can make counts towards lesser warming, and thus more manageable impacts: smaller losses in tropical crop yields, fewer people forced to leave their homes, and fewer premature deaths, to name a few. Climate anxiety is a real phenomenon. Doomist reporting doesn’t help with this and may even lead to less action, as exemplified in the framing of this question.

It is not possible to get enough protein or all the needed nutrients from vegetarian or vegan diets: It is true that vegans need to take B12 and D supplements (in fact, everyone in Finland should take vitamin D supplements as we don’t get enough from the sun), as well as use products fortified with micronutrients. But as long as this is taken care of, it is by all means possible to get everything necessary even from vegan diets. However, changing habits always requires some extra effort and when speaking of diets it can feel quite taxing to seek information and try new foods. It can be easier to achieve your dietary goals by changing your habits little by little. Also, on a public health level, there is the danger that too radical changes in recommendations may have unwanted consequences. Not everyone has the resources to learn about new diets and foods. Simply dropping meat from an already non-ideal diet without proper replacements might do more harm than good with respect to health.

Did you know that...

- One third of the food produced globally is lost during production or wasted at the point of consumption.

- If everyone ate according to existing food recommendations, greenhouse gas emissions from food would decrease by 30-70 % by 2050.

- Globally 50 % of ice-free land is used for agriculture. Of all agricultural land, 80 % is used for growing livestock (when you include the food produced for them).

- As opposed to plant-based products, dairy and meat have on average an order of magnitude greater water footprint (add a zero to the end).

- Worldwide, agricultural lands are dominated by only four crops: wheat, rice, soybean and corn.

- In Finland, meat consumption per capita has doubled over the past 60 years.

- Over the past few decades catch from marine fisheries has been declining due to overfishing. Information on choosing sustainable fish and seafood can be found here

ACknowledgements

Special thanks to Usha and Noora-Helena from the Science Basement writing workshop for your encouragement and great suggestions on the early versions of the text, to our parents Outi, Eva, Matti and Anssi for providing either encouragement, critique, grammar corrections and helpful suggestions on the nearly final version of the text or for providing quiet space for writing, to Jaakko for running through the text and for being an inspirational figure for public health research and outreach, to the reviewers for their helpful comments, and finally to our pumpkin for being our main driver for writing on topics like this.

References and further material

Videos

Clay, J. (Director). (2021). Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet [Film; Netflix Documentary]. Silverback Films.

Podcasts

Journalism and web content

UNEP. (2020, July 13). How to feed 10 billion people.

Asher, C. (2021, March 30). The nine boundaries humanity must respect to keep the planet habitable. Mongabay.

Stockholm Resilience Center. (n.d.) The nine planetary boundaries.

EAT-Lancet Commission. (n.d.) The EAT-Lancet Commission Summary Report.

EAT Forum The EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, Health

In Finnish: Laatikainen, R. (2019, January 28). Maapallolle terveellinen ruokavalio muuttaisi suomalaisten ravintoaineiden saantia ja ruoka-aineiden kulutusta. Pronutritionist.

Sigal. S. (2020, August 20). The meat we eat is a pandemic risk, too. Vox.

Vidal, J. (2021, October 18). Factory farms of disease: how industrial chicken production is breeding the next pandemic. The Guardian.

The Nutrition Source. (2014, January 24). The problem with potatoes.

Preview version of the University of Helsinki Sustainability Course 2022 (n.d.). Module D: Sustainable food systems and healthy nutrition.

In Finnish: Ilmasto-opas. (2020, May 12). Ilmastonmuutosta voi hillitä ilmastoystävällisellä ruokavaliolla.

Mann, M. (2017, July 12). Doomsday scenarios are as harmful as climate change denial. The Washington Post.

Ritchie, H. & Roser, M. (2017, August). Meat and Dairy Production. Our World in Data.

Vaidyanathan, G. (2021). What humanity should eat to stay healthy and save the planet. Nature, 600(7887), 22-25.

Garcia, D., Galaz, V., & Daume, S. (2019). EATLancet vs yes2meat: the digital backlash to the planetary health diet. The Lancet, 394(10215), 2153-2154.

Books

In Finnish: Auvinen, S. (2020). Lihan Loppu. Kosmos.