The Planetary Boundaries: Have we pushed our planet to the limit?

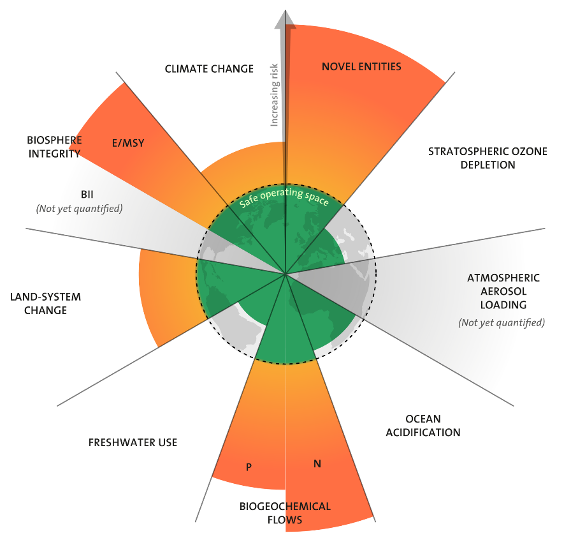

“It is a planetary emergency,” says world-renowned Professor Johan Rockström in his 8-min TED Talk from 2020: 10 years to transform the future of humanity – or destabilize the planet. A decade earlier, in 2009, Rockström and colleagues had identified planetary boundaries for nine dimensions of the Earth system (Figure 1). These define the so-called safe operating space for humanity on Earth. If we cross these boundaries, we risk crossing tipping points for crucial Earth systems like glaciers (which are melting) or tropical forests (which can turn into savannah), and thereby triggering irreversible and catastrophic environmental changes. The dimensions of the framework are deeply intertwined, and tipping points could topple like dominoes.

The exact boundaries within the nine dimensions of the framework are hard to pinpoint due to the complexity of the Earth system. However, in their study, the group establishes for each of them an uncertainty range (not in Figure 1, but often represented in yellow), beginning at “safe” and ending at the beginning of the “danger zone”. As a precaution, the boundary is set at the lower limit of this uncertainty range. As long as we stay below the boundary, we are safe. If we cross it, we risk a higher and higher chance of unwanted changes. As of 2022, we have already crossed five out of nine of the planetary boundaries (Figure 1). We are walking in a minefield, holding our breath with every step.

“This is the countdown. […] The fossil fuel era is over. […] The good news is, we can do this. We have the knowledge. We have the technology. We know it makes social and economic sense,” Rockström ends his alarming speech with hope.

Figure 1. Planetary boundaries diagram showing that we have crossed five out of the nine planetary boundaries. Credit: Designed by Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Persson et al. 2022 and Steffen et al. 2015.

The Planetary Health Diet: Can we feed the world without destroying it?

So we’ve pushed our planet to its limits. What do we do now? How do we ensure a healthy planet? You’re probably thinking: “Renewables! We quit using fossil fuels and emitting greenhouse gases.” Yes, unarguably, we need an energy reform urgently. That is the number one priority. Nevertheless, if you look at the planetary boundaries framework, greenhouse gas emissions affect only two of the boundaries directly: climate change and ocean acidification. And even for just addressing climate change, giving up fossil fuels will not be enough. Just as importantly –and pressingly, we need a food system reform. We need to focus on both the reduction of fossil fuel emissions and the changing of diets to meet the historic Paris Agreement climate target: to keep the global mean temperature increase below 2 degrees Celsius and closer to 1.5 degrees Celsius (relative to 1861–80 temperatures) in this century.

What’s more, food production touches at least six of the nine planetary boundaries. It is the largest driver behind global environmental change: it is the biggest culprit for biodiversity loss, among the biggest sources of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, accounts for 70 % of freshwater use, 40 % of land use, and one third of all greenhouse gas emissions. Food packaging, herbicides and pesticides again contribute to chemical pollution, and thus impact the novel entities boundary.

Our current dietary patterns are not only a risk to our planet but also to ourselves. Globally, 25 % of the population is overweight or obese, mainly a problem of the Western World. At the same time, over 10 % is undernourished, mainly in low- and middle-income countries. In addition, regardless of weight, 25 % of us suffer from deficiencies of essential nutrients. Poor diet causes more deaths and disability worldwide than any other risk factor.

Fortunately, though still a major public health concern, we are headed in the right direction when it comes to solving undernutrition. However, the same cannot be said about obesity and suboptimal diet. Based on the Global Burden of Disease Study from 2017, diseases such as cardiovascular disease, some cancers and type 2 diabetes, resulting from poor diet, were the cause of one in five adult deaths. Globally, we are eating too much salt, and too little fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Additionally, in the Western World, we are consuming more red and processed meat than recommended, to an extent that is not healthy.

As the global population is projected to reach 10 billion by 2050 (from its current 7.7 billion), and increasing numbers of people are eating like Westerners, without a food system reform, the production of meat, dairy and eggs will need to rise by about 44 % by 2050. Now, this poses a problem. Animal-based foods produce twice the amount of emissions as plant-based foods and require lots more land and water. Continuing on this path, we simply will not have enough food for everyone. We run into issues not only of health and environment but also of equity, ethical responsibility and political stability.

In 2014, the Norwegian doctor Gunhild Stordalen asked: How is it possible to feed the world healthy food without destroying the planet? She searched the existing literature but there was no scientific consensus on what a healthy diet from a sustainable food system looked like. Despite increasing recognition of the food system being broken, there was no plan in place on how to fix it. She then turned to Johan Rockström, and together with the Stockholm Resilience Centre, they founded the EAT Initiative, a global non-profit organization working to reform the food system. Soon after, they had a team of 37 world-leading scientists putting together the puzzle of a sustainable and healthy diet.

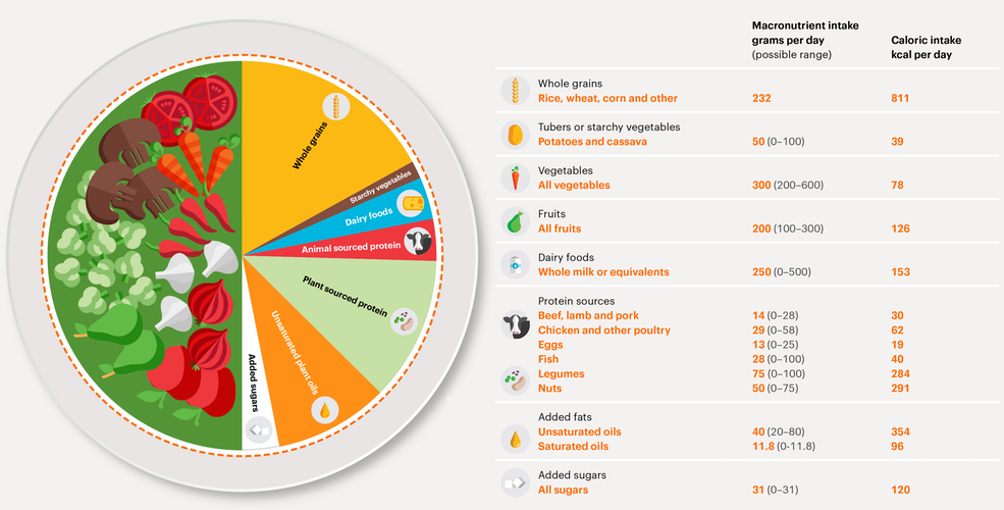

The scientists published their results, the EAT-Lancet report, in the leading medical journal the Lancet in 2019. They essentially performed an extensive review of hundreds of publications and put together a win-win, healthy and environmentally sustainable, reference diet. This is the planetary health diet (called the healthy reference diet in the report). This diet largely consists of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, plant-based protein sources (beans, lentils, peas, soy foods, peanuts, tree nuts), and unsaturated oils, includes no, or at the most a moderate amount, of seafood and poultry, and includes no or little red meat, processed meat, added sugar, refined grains, and starchy vegetables. It is a flexitarian diet, allowing for adaptation to dietary needs, cultural traditions and personal preferences. In their recommendations, they include ranges for different food categories, not totally banning anything (Figure 2). They emphasize that it is not a one-size-fits-all diet and may look different for people living in Finland or Japan, and allows for various types of omnivore, vegetarian, and vegan diets. The greatest difference to most previous dietary guidelines is in the protein sources, in which they emphasize plant-based sources. It is very much in line with the traditional Mediterranean diet, in which meat was reserved for special occasions. Regarding animal protein, their reference diet would include roughly one serving of red meat, one serving of chicken, two servings of fish and two eggs per week.

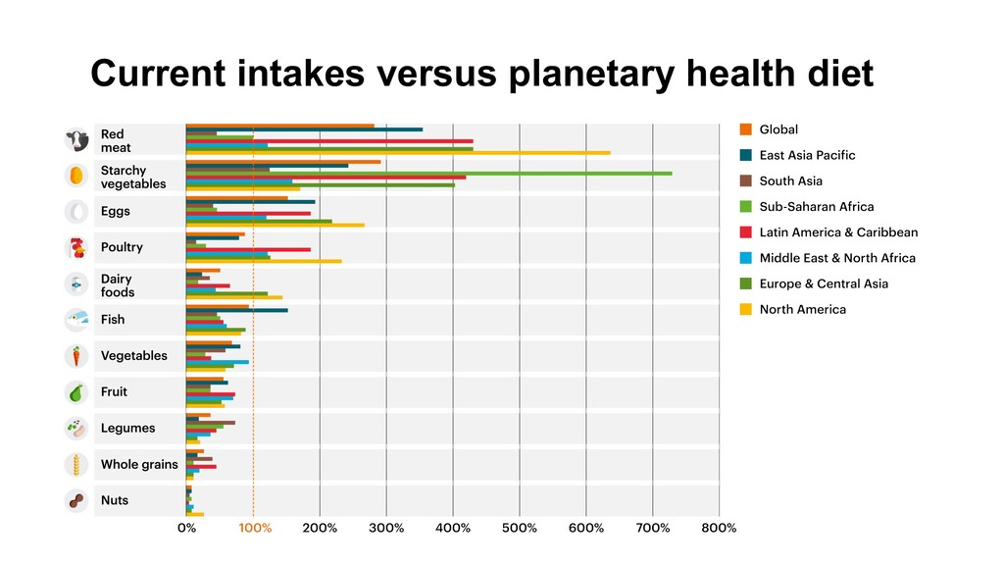

To visualize what the planetary health diet looks like, EAT has created a food plate illustrating it (Figure 2). Currently, in the Western countries, we are consuming 4-6 times more red meat than the recommended amount in the planetary health diet (Figure 3). We are also overconsuming all other animal products aside from fish, only eating half of the vegetables and fruits and only a speck of nuts, legumes and whole grains as compared to the planetary health diet. It looks like we need to learn how to eat again. This may seem daunting, but what a great opportunity to improve our health and wellbeing! The authors of the EAT-Lancet report estimate that with this diet we could save 11 million premature adult deaths annually.

Figure 3. Diet gap between dietary patterns in 2016 and reference diet intakes of food. The dotted line represents intakes in reference diet (Figure 2). Source: The Lancet, EAT-Lancet Report.

ACknowledgements

Special thanks to Usha and Noora-Helena from the Science Basement writing workshop for your encouragement and great suggestions on the early versions of the text, to our parents Outi, Eva, Matti and Anssi for providing either encouragement, critique, grammar corrections and helpful suggestions on the nearly final version of the text or for providing quiet space for writing, to Jaakko for running through the text and for being an inspirational figure for public health research and outreach, to the reviewers for their helpful comments, and finally to our pumpkin for being our main driver for writing on topics like this.

References and further material

Videos

Clay, J. (Director). (2021). Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet [Film; Netflix Documentary]. Silverback Films.

Podcasts

Journalism and web content

UNEP. (2020, July 13). How to feed 10 billion people.

Asher, C. (2021, March 30). The nine boundaries humanity must respect to keep the planet habitable. Mongabay.

Stockholm Resilience Center. (n.d.) The nine planetary boundaries.

EAT-Lancet Commission. (n.d.) The EAT-Lancet Commission Summary Report.

EAT Forum The EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, Health

In Finnish: Laatikainen, R. (2019, January 28). Maapallolle terveellinen ruokavalio muuttaisi suomalaisten ravintoaineiden saantia ja ruoka-aineiden kulutusta. Pronutritionist.

Sigal. S. (2020, August 20). The meat we eat is a pandemic risk, too. Vox.

Vidal, J. (2021, October 18). Factory farms of disease: how industrial chicken production is breeding the next pandemic. The Guardian.

The Nutrition Source. (2014, January 24). The problem with potatoes.

Preview version of the University of Helsinki Sustainability Course 2022 (n.d.). Module D: Sustainable food systems and healthy nutrition.

In Finnish: Ilmasto-opas. (2020, May 12). Ilmastonmuutosta voi hillitä ilmastoystävällisellä ruokavaliolla.

Mann, M. (2017, July 12). Doomsday scenarios are as harmful as climate change denial. The Washington Post.

Ritchie, H. & Roser, M. (2017, August). Meat and Dairy Production. Our World in Data.

Vaidyanathan, G. (2021). What humanity should eat to stay healthy and save the planet. Nature, 600(7887), 22-25.

Garcia, D., Galaz, V., & Daume, S. (2019). EATLancet vs yes2meat: the digital backlash to the planetary health diet. The Lancet, 394(10215), 2153-2154.

Books

In Finnish: Auvinen, S. (2020). Lihan Loppu. Kosmos.