The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Sides of Oestrogen

Zsofia Hesketh is an interdisciplinary scholar and public health professional with a background in philosophy, medical research, and clinical medicine. She is completing her MSc Translational Medicine as a visiting student at Sorbonne Médecine, Paris, where she is focusing on gynaecology and neglected aspects of women’s health.

This article is part of the intersections theme.

edited by Kenia & heini, reviewed by sophie bracke, illustrated by kenia & sophie hoetzel.

Instructional scrolls dating back to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia describe contraceptive methods that might seem unreliable, if nothing else, to us today, such as mixing of honey with acacia and applying the mixture to the cervix as a spermicide. Advances in contraception have, since those ancient times, played a critical role in improving women’s reproductive rights and enabled them to make informed decisions about their bodies and lives. However, some of these methods come with a price, the severity of which is only starting to be taken seriously now.

Curious? Let’s talk about the good, the bad, and the ugly sides of oestrogen-based contraception, such as the pill.

The freedom to choose…

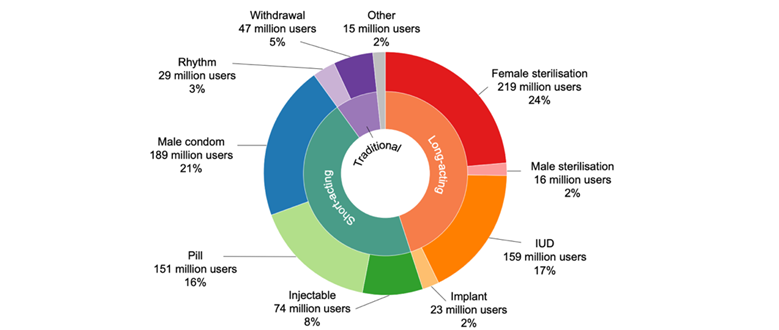

In today’s world, we have more choices than ever over which contraceptive method to use, most of them being hormone-based. Though condoms have been around for longer, the oldest modern pharmacological method is the oral contraceptive pill, typically composed of a mixture of the hormones oestrogen and progestin. Known as “combined pills”, these work to prevent ovulation, which is the release of an egg from the ovaries. Without ovulation, there is no egg for the sperm to fertilise, effectively preventing pregnancy.

Among non-oral methods are the implant, a small rod inserted under the skin, and the Depo injection, which are progestin-based and offer years or months of protection respectively, being more prevalent among older women who wish to stop having children. Intrauterine devices (IUDs) can either be hormonal, releasing progestin directly into the uterus, or made of copper, which is toxic to sperm. Last but not least are condoms, a non-invasive barrier also effective against many STDs, and sterilisation – surprisingly the most popular method on the global scale, especially in Latin America and South Asia.

Access to modern pharmacological contraception was first approved in 1960 by the United States FDA. They authorised the use of Enovid, the first combined oestrogen-progesterone pill. At this point, access was granted to married women and those who did not want to have more children. The message was clear: contraception was intended as a family-planning tool rather than a measure for women to control their bodies and fertility. Despite this, the pill rapidly gained popularity and was soon made available more widely, its consumption correlating with increased female university attendance and graduation rates.

Less than a decade later, in 1967, a pioneering development establishing legal protections for women seeking contraception was introduced in France through the “loi Neuwirth” or “Neuwirth law”, which legalised access to oral contraceptive pills. Following the activism of prominent lawyer, politician, and women’s rights trailblazer Simone Veil, the law was expanded in 1974 to making emergency or ‘morning after’ pills available to women without a prescription. This ensured that even in times of unexpected, urgent need, women could make their own choice without interference. These laws were crucial for individual women’s rights but equally fostered broader societal dialogue about the importance of gender equality and bodily autonomy.

Enovid, mentioned above in the US context, was an example of a combined pill, though it contained much higher doses of oestrogen than brands currently in use. Some contraceptive pills, called “mini pills”, include only the hormone progestin and serve as an alternative for those who cannot take oestrogen, like women with vascular or neurological contraindications. These types of pills are prescribed less frequently for patients without such contraindications due to stricter timing requirements and lower efficacy, though studies in the last decade suggest higher protection rates than previously thought.

The development of a wide range of contraceptive options has given women greater control over their fertility and provided them with access to relatively effective methods for preventing unintended pregnancy. Unfortunately, despite the widespread use of hormonal methods for several decades and their undeniable societal importance, evidence suggests that long-term hormonal supplementation – particularly of oestrogen – can damage a woman’s health. The active compounds in common contraceptives, especially of the orally-taken variety, therefore merit a closer look.

… but not without trade

As described above, hormonal contraceptives take several forms and are either a combination of oestrogen-progestin or progestin-only. Let’s focus on the oestrogen component, whose safety profile is a lot more ‘colourful’ than progestin’s. Oestrogen, which governs the development of secondary female sex characteristics, exists in several forms. We will be discussing two of these, ethinylestradiol and estradiol, in more detail. Buckle up!

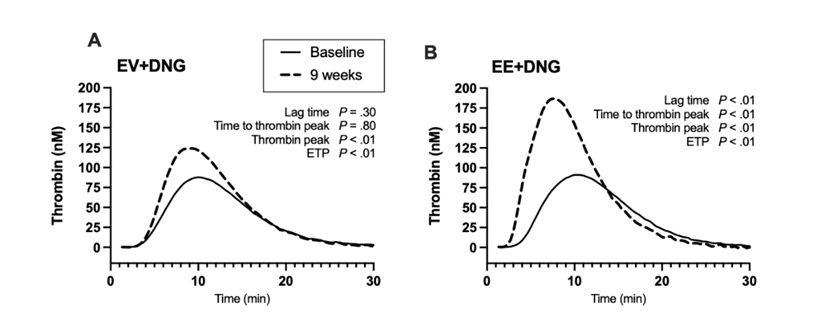

Ethinylestradiol is a laboratory-modified oestrogen that remains the most common form present in birth control pills. While performing excellently in its contraceptive function, the hormone also triggers blood clotting factors, proteins that help your body form blood clots to, for example, stop bleeding when you get injured. These clots can obstruct blood flow and lead to a higher risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), one of the most serious and documented side effects of combined hormonal contraceptives. For example, Yasmin, Yaz, and Rigevidon, three contraceptive pill brands all containing ethinylestradiol, have all fallen from grace due to repeated incidents involving blood clotting. In DVT, the blood clotting most often affects veins in the legs but can also occur in blood vessels of the upper body and the brain, leading to an increased risk of stroke.

Due to the side effects, the ethinylestradiol dose in various contraceptive pills has been reduced over time from 100 to 20–30 micrograms, resulting in a lowered risk of blood clotting. The oestrogen formulation in tablets has also started to change, leaning more towards another form of oestrogen: estradiol, a natural oestrogen produced by the body, which is thought to cause more moderate side effects. A recent doctoral thesis by Annina Haverinen shows much lower coagulation effects of contraceptives with this version of the hormone. However, it is still apparent that all forms of oestrogen carry some vascular risk (see Figure 3 below).

Linked to this, a more well-known contraindication of oestrogen-based contraceptives is their risk for those that suffer from migraines with aura (NHS Foundation Trust). Migraines are a type of pulsating headache that can last from several hours to several days, often accompanied by nausea and sensitivity to light and sound. Some people also experience sensory disturbances or “aura” right before or during the onset of the pain, typically as flashing lights or blind spots in their vision. These patients already have a higher baseline chance of stroke, and oestrogen’s blood clotting tendency only adds to the risk.

It’s scary how little we know, right? What’s more, we tend to be equally badly informed about gynaecological conditions for which hormonal contraception is used, chief among these being endometriosis. Let’s dig a bit deeper…

Endometriosis, so overlooked it hurts

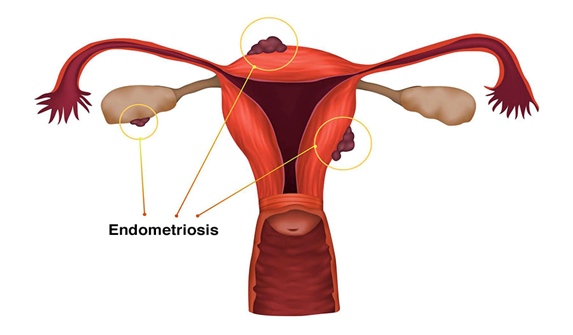

Birth control pills are often prescribed to people with endometriosis because they can help regulate the menstrual cycle and reduce the growth of endometrial tissue outside the uterus, which is the hallmark characteristic of this condition.

In endometriosis, the tissue that normally lines the inside of the uterus (the “endometrium”) grows outside of it, extending towards the ovaries, fallopian tubes, cervix, and even other pelvic organs like the bowel and bladder (figure 4). Misplaced endometrial tissue in these areas does not shed during a menstrual cycle like healthy endometrial tissue inside the uterus does. Rather, it responds to cyclical changes in oestrogen and progesterone balance with inflammation, scarring, severe chronic pain, heavy or irregular periods, bloating, and gastrointestinal flare-ups. Furthermore, evidence points to these symptoms being the tip of the iceberg, with Yale gynaecologists asserting that the condition is systemic and “goes far beyond the pelvis“. In other words, the misplaced tissue might migrate to more distant organs, carried out from the uterus by blood or lymphatic circulation towards the bowels, bladder or kidneys.

Although the cause of endometriosis is not fully understood, it affects an estimated 5-10% of reproductive-aged women worldwide. To put this number in context, compare it with diabetes, with a 9.3% prevalence. This makes it one of the most common gynecological conditions. It can occur in girls as young as eight years old and persist until menopause, though symptoms may improve or worsen over time. Contraceptive pills may be prescribed with varying success to alleviate symptoms by slowing down the process of tissue migration.

Despite its severity, high prevalence, and individual and societal burden, it is estimated that 65% of women with endometriosis have been initially misdiagnosed and that successful diagnosis takes between 4 and 11 years. Just think about living for that long, with no relief in sight, feeling like your guts are regularly wrung out like a wet towel! This is no exaggeration – teenage girls and women with endometriosis have described their experience as “getting stabbed”, “being bedridden with pain”, and “a barbed wire fence running across my abdomen”. Pretty evocative, huh? If you’re interested in experiencing some phantom abdominal pain by reading an even wider collection of patient descriptions, I highly recommend checking out testimonials on Endometriosis.net.

Endometriosis research funding remains below that of certain rare pregnancy-related conditions, constituting for example just 0.038% of the 2022 research budget of the National Institutes of Health. For a condition that affects over 190 million worldwide, this strikes as quite a weak push to learn more. Plus, much of the attention that is directed to endometriosis has come from the condition’s significant contribution to infertility rather than exploring its consequences on nearby organs or, well, the elephant in the room that is the pain. This amplifies the feeling that women’s health is perceived to be more important when related to procreation and that guaranteeing an existence free of pain for women as individuals is a lesser priority.

The power of awareness

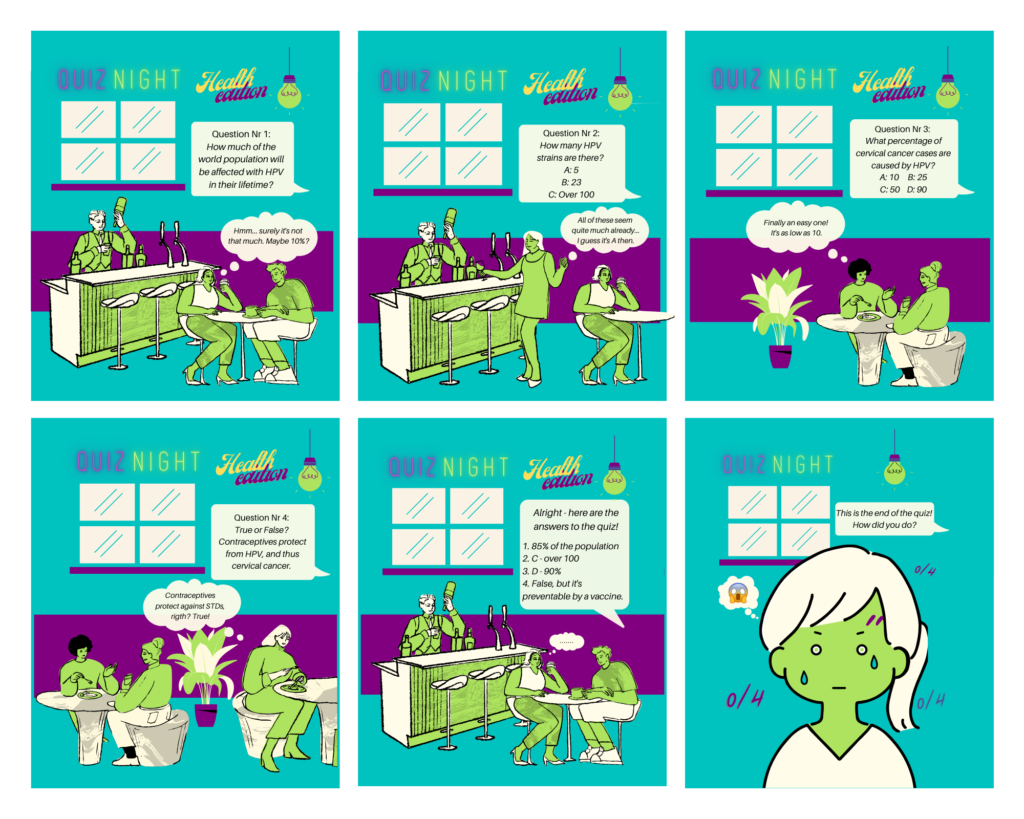

Women of reproductive age (including teenagers) are proposed birth control pills routinely, sometimes without being informed of their possible side effects, risks and their inefficacy against sexually transmitted pathogens like HPV.

The notion that women alone are accountable for their fertility and pain while being provided options of dubious safety or efficacy is senseless. To acknowledge the risks and side effects of hormonal contraceptives is not to contravene the tremendous advancement of reproductive control and autonomy that they have offered. Rather, it serves as a signal to expand our awareness of them, as women too often receive insufficient guidance and counselling about what might be happening inside their bodies.

We must also distinguish between ‘risks’ and ‘side effects’ as linked to contraceptives. The risk of developing a condition, such as venous thromboembolism, may be increased by birth control pills and represents the possibility of a potential future event occurring. Meanwhile, a side effect refers to a more immediately-occurring symptoms that are directly caused by taking a medication, in this case headaches, breast tenderness, and bloating to name just a handful. As for ‘risk factors’, these are patient attributes originating from pre-existing lifestyle or medical circumstances that modulate the chances of them experiencing negative effects from contraceptives or other drugs.

Considering the severity of certain risks, risk factors and side effects, we can’t stop here. We need to keep striving for safer and better methods that are thoroughly tested prior to market approval and subject to regular evidence-based reviews. While doing so, R&D funding bodies must take the opportunity to encourage and enhance our understanding of related conditions like endometriosis.

Migraine, mentioned as a risk factor for birth control complications, is a common neurological condition in women. Interested in learning more? Join us in the next instalment of this article series on female health, dedicated to the mysteries of nervous system sex differences.

references

Ellis, Katherine, et al. “Endometriosis Is Undervalued: A Call to Action.” Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, vol. 3, 10 May 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.902371″ https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.902371.

Editorial Team, Endometriosis.net. “What Does Endometriosis Pain Feel Like?” 2021. https://endometriosis.net/living/pain-description

Fraser, Ian, and Edith Weisberg. “Contraception and Endometriosis: Challenges, Efficacy, and Therapeutic Importance.” Open Access Journal of Contraception, July 2015, p. 105, www.dovepress.com/articles.php?article_id=22806%22%20target=%22_blank%22, https://doi.org/10.2147/oajc.s56400.

Glasier, Anna, et al. “A Review of the Effectiveness of a Progestogen-Only Pill Containing Norgestrel 75 Μg/Day.” Contraception, Sept. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2021.08.016.

Goldin, C. and Katz, L. “The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career and Marriage Decisions” August 2002. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 11, No.4. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/2624453/Goldin_PowerPill.pdf

Guibert-Lantoine, Catherine, and Henri Leridon. “Contraception in France. An Assessment after 30 Years of Liberalization.” Population: An English Selection, vol. 11, 1999, pp. 89–113, www.jstor.org/stable/2998691.

Hall, Kelli Stidham, et al. “Progestin-Only Contraceptive Pill Use among Women in the United States.” Contraception, vol. 86, no. 6, Dec. 2012, pp. 653–658, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2012.05.003.

Haverinen, A. Estradiol valerate vs. ethinylestradiol in combined oral contraception: effects on metabolism, reproductive hormones and blood coagulation. 2022. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/347277/Haverinen_Annina_dissertation_2022.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Ismail, N.H. et al. “Augmentation of the Female Reproductive System Using Honey: A Mini Systematic Review.” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 3, 1 Jan. 2021, p. 649, www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/26/3/649, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26030649.

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L; World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium. Consensus on current management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(6):1552-1568. doi:10.1093/humrep/det050.

Masih, Ni. “Need time off work for period pain? These countries offer ‘menstrual leave”‘ https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/02/17/spain-paid-menstrual-leave-countries/

NHS Foundation Trust. “Contraception Information: Migraines and Combined Hormonal Contraceptives.” https://www.oxfordhealth.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CY-193.17-migraines-and-combined-hormonal-contraceptives.pdf

Saeedi, Pouya, et al. “Global and Regional Diabetes Prevalence Estimates for 2019 and Projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th Edition.” Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, vol. 157, no. 157, Sept. 2019, p. 107843, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31518657/, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843.

Samani, Elham N., et al. “Micrometastasis of Endometriosis to Distant Organs in a Murine Model.” Oncotarget, vol. 10, no. 23, 6 Apr. 2017, pp. 2282–2291, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16889.

Stegeman, B. H., et al. “Different Combined Oral Contraceptives and the Risk of Venous Thrombosis: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis.” BMJ, vol. 347, no. sep12 1, 12 Sept. 2013, pp. f5298–f5298, www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f5298, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f5298.

Taylor, H. S., Kotlyar, A. M., & Flores, V. A. “Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations.” The Lancet, 397(10276), 839–852. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00389-5

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.”Contraceptive Use by Method 2019, Data Booklet”, 2019.

Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. “Endometriosis”. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13) :1244-1256. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1810764.